Writing a RAM-backed block driver in the Linux Kernel

Linux block layer stack is a complicated beast as it needs to cater to all use cases, but it also allows a block device driver writer to focus only on dealing with the complexity of the device. This article explores a simple RAM-backed block device driver module in the Linux Kernel. The main idea of this article is to show the framework the block layer provides to write a device driver in the kernel land.

A simple block driver: blkram that lives in the RAM will be

written from scratch as a part of this article. I

decided to do this to focus on the block layer stack with a practical

example without having to deal with the complexity of

an actual block device such as a SATA or an NVMe drive. Maybe in the

future, I will explore writing an NVMe driver from scratch in the kernel.

Linux Block layer is constantly being innovated and modified. As there are no API/ABI guarantees within the kernel, the code that is shown in this article which is based on Linux 6.1.0-rc6 might be outdated in a year.

Linux Block layer

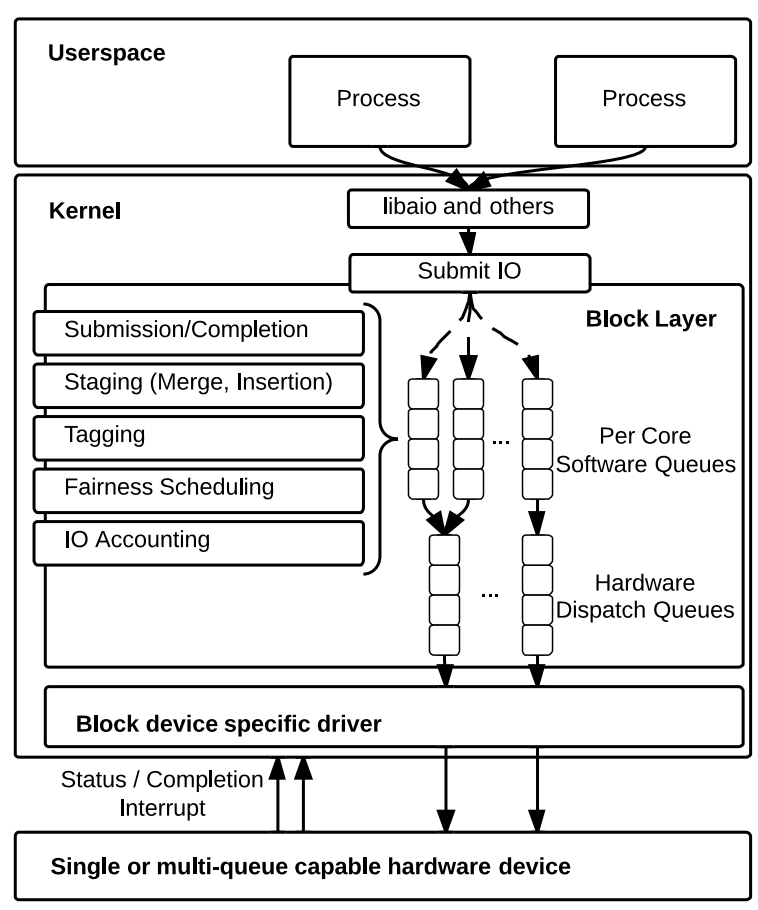

The Linux Block layer introduced blk-mq framework around 2013. All the

new block drivers are required to use this framework. Some drivers still use older frameworks

in the kernel, but most of the drivers have been modified to be consistent.

The following picture taken from paper shows

how the block layer stack with blk-mq works1

|

|---|

| Block layer stack |

The blk-mq uses a two-layer multi-queue design where software queues

based on the number of cpu cores are mapped to a hardware queue/queues.

The primary rationale behind this design is to allow a block device driver

to fully use the multiple hardware queues present in modern

devices such as NVMe SSD. Older devices with a single queue can map all the

software queues to a single hardware queue. The blkram driver will

also use a single hardware queue. The reader can find more information

about blk-mq from this paper and this

LWN article.

BLKRAM driver

blkram is an out-of-tree kernel module using the blk-mq framework and do read & writes

in the memory(RAM) that will be written as a part of this article.

The code can be found here on Github.

Module:

Before talking about the initialization, we need to talk about a

kernel module. module_init and module_exit needs to be defined that

are automatically called when a module is loaded and unloaded

respectively:

module_init(blk_ram_init);

module_exit(blk_ram_exit);

To store the relevant information of the driver, a new structure

blk_ram_dev is introduced, which has the following members:

struct blk_ram_dev_t {

sector_t capacity;

u8 *data;

struct blk_mq_tag_set tag_set;

struct gendisk *disk;

};

The capacity holds the capacity of the block device in sectors (512

bytes), and data will contain the pointer to the actual block of memory

backing the block device. The blk_mq_tag_set and gendisk

structure will be explained in more depth later.

The capacity/size of the driver is exported as a module parameter, and it can be set while loading the module:

// To change the default: insmod blkram.ko capacity_mb=80

unsigned long capacity_mb = 40;

module_param(capacity_mb, ulong, 0644);

MODULE_PARM_DESC(capacity_mb, "capacity of the block device in MB");

As this driver is not associated with a lower-level driver such as

PCI, a pointer to the struct blk_ram_dev_t needs to be stored as a

static variable in the module:

static struct blk_ram_dev_t *blk_ram_dev = NULL;

Initialization:

The initialization code of the driver goes under the blk_ram_init

function.

The register_blkdev function is first called to get a major number for

the block device. This is an optional function to call. We store the

major number as a static module parameter as it will be used again in

blk_ram_exit function to clean up.

Memory is allocated for the struct blk_ram_dev_t using kzalloc.

kzalloc allocates the memory in RAM and initializes it with zero

(similar to kmalloc with memset(0)). After this, memory needs to be

allocated for the RAM memory backing the block device. A

default value of 40 MB is chosen here.

kvmalloc is used to allocate that memory as the value is considerable.

kvmalloc function tries to allocate physically contiguous memory and

if that fails, then it allocates virtually contiguous memory which might

not be physically contiguous. Having a physically discontiguous memory

should not be an issue for this driver. Besides, the kernel does not

allow using kmalloc for requested capacity than a certain limit.3

// Omitted error handling

blk_ram_dev = kzalloc(sizeof(struct blk_ram_scratch_dev), GFP_KERNEL);

blk_ram_dev->data = kvmalloc(data_size_bytes, GFP_KERNEL);

...

Setting up the request queue:

Request queue must be configured before setting up the disk parameters. I think

of Request queue as the data plane where the actual data is transferred to

the device and disk abstraction is the control plane(struct gendisk) of a block

device.

struct blk_mq_tag_set is used by the block driver to configure

request queue with the number of hardware queues, queue depth, callbacks, etc. This

structure does a lot more than just store these parameters. It also

has tags, which track requests sent to a block device. The

code below sets up the tag_set data structure:

// Omitted error handling

memset(&blk_ram_dev->tag_set, 0, sizeof(blk_ram_dev->tag_set));

blk_ram_dev->tag_set.ops = &blk_ram_mq_ops;

blk_ram_dev->tag_set.queue_depth = 128;

blk_ram_dev->tag_set.numa_node = NUMA_NO_NODE;

blk_ram_dev->tag_set.flags = BLK_MQ_F_SHOULD_MERGE;

blk_ram_dev->tag_set.cmd_size = 0;

blk_ram_dev->tag_set.driver_data = blk_ram_dev;

blk_ram_dev->tag_set.nr_hw_queues = 1;

ret = blk_mq_alloc_tag_set(&blk_ram_dev->tag_set);

disk = blk_ram_dev->disk =

blk_mq_alloc_disk(&blk_ram_dev->tag_set, blk_ram_dev);

blk_queue_logical_block_size(disk->queue, PAGE_SIZE);

blk_queue_physical_block_size(disk->queue, PAGE_SIZE);

blk_queue_max_segments(disk->queue, 32);

tag_set.ops provides the callbacks to blk_mq. One

important callback that needs to be set for this driver is queue_rq.

This callback is called whenever a request is ready to be processed by

the device driver. More about queue_rq later in the article.

tag_set.flags is used to set certain request queue properties.

BLK_MQ_F_SHOULD_MERGE flag is set to let the block layer to merge

contiguous requests together:

if (!(hctx->flags & BLK_MQ_F_SHOULD_MERGE) ||

list_empty_careful(&ctx->rq_lists[type]))

goto out_put;

...

/*

* Reverse check our software queue for entries that we could

* potentially merge with. Currently includes a hand-wavy stop

* count of 8, to not spend too much time checking for merges.

*/

if (blk_bio_list_merge(q, &ctx->rq_lists[type], bio, nr_segs))

ret = true;

tag_set.nr_hw_queues is an important parameter that is used to inform

the block layer about the number of hardware queues this device can

support. In the case of blkram, only one hardware queue is chosen. For

NVMe devices which can physically support multiple hardware queue,

tag_set.nr_hw_queues can be given a higher value and

blk_mq_map_queues can map SW queues to the HW queues.

A tag_set is allocated with blk_mq_alloc_tag_set call with the

respective parameters. A request queue can be created with the

corresponding tag_set by calling blk_mq_alloc_disk function. This

function only allocates a disk but does not “add” it to the system.

struct gendisk contains a reference to the request queue that can be

used to configure parameters such as logical_block_size,

physical block size, etc.(block settings can be explored in this file

block/blk-settings.c).

Setting up the disk:

The gendisk structure stores the relevant context about a block device with

its bookkeeping information such as name, major/minor number,

partitions, etc. The struct gendisk can be found in blkdev.h. As

mentioned earlier, one could think of it as the control plane of a block

device.

disk->major = major;

disk->first_minor = minor;

disk->minors = 1;

snprintf(disk->disk_name, DISK_NAME_LEN, "blkram", minor);

disk->fops = &blk_ram_rq_ops;

disk->flags = GENHD_FL_NO_PART;

set_capacity(disk, blk_ram_dev->capacity);

ret = add_disk(disk);

Major number identifies the driver associated with a device, and minor identifies the exact device that belongs to the driver so that the device can be differentiated. For example in block devices, different partitions are given a different minor number, but the major number will remain the same.

As it is just a simple block driver, I decided not to support any

partitions. GENHD_FL_NO_PART flag is set to the disk to tell the block

layer not to scan for any partitions. Similarly, minors is set to 1

as there will be no partitions. Block layer code that checks for

GENHD_FL_NO_PART and skip scanning for partitions:

static int blk_add_partitions(struct gendisk *disk)

{

if (disk->flags & GENHD_FL_NO_PART)

return 0;

state = check_partition(disk);

...

disk->fops contains all the callbacks for the block device that is

used to perform open, release, ioctl, etc. The following snippet

should be enough for the blkram driver as we don’t need to do anything

special:

static const struct block_device_operations blk_ram_rq_ops = {

.owner = THIS_MODULE,

};

Finally, calling add_disk should create a block device /dev/blkram.

Request processing:

queue_rq callback is called by the block layer to process a request by

the device driver. Typically, queue_rq callback is used by a driver to

send the commands to a device, and the command completion is notified by

an interrupt request. As this block driver is dealing with RAM, which has low

latency, requests can be completed synchronously in the queue_rq

callback.

static blk_status_t blk_ram_queue_rq(...)

{

loff_t pos = blk_rq_pos(rq) << SECTOR_SHIFT;

struct bio_vec bv;

struct req_iterator iter;

blk_status_t err = BLK_STS_OK;

....

blk_mq_start_request(rq);

rq_for_each_segment(bv, rq, iter) {

unsigned int len = bv.bv_len;

void *buf = page_address(bv.bv_page) + bv.bv_offset;

...

switch (req_op(rq)) {

case REQ_OP_READ:

memcpy(buf, blkram->data + pos, len);

break;

case REQ_OP_WRITE:

memcpy(blkram->data + pos, buf, len);

break;

default:

err = BLK_STS_IOERR;

goto end_request;

}

pos += len;

}

end_request:

blk_mq_end_request(rq, err);

return BLK_STS_OK;

}

blk_mq_start_request is called first to inform the block layer that

the driver has started processing the request. This is important for the

block layer to do accounting and keep track of each request for a

potential timeout.

rq_for_each_segment is used to iterate over all the segments in a

request and perform any operation on a bio_vec (block IO vector). Only read

and write are supported by the blkram driver. When the request is

REQ_OP_READ, then a memcpy is performed from the data (backing

store of this block device) to the page given the bio_vec, and vice

versa for REQ_OP_WRITE.

blk_mq_end_request is called with the appropriate err to mark that

the request is now completed. In NVMe devices, this function is called as a part of the

interrupt request when the device signals its completion of a command.

Testing:

The driver is now ready to be tested. The module can be loaded as follows:

$ insmod blkram.ko capacity_mb=80

$ lsblk | grep blkram

blkram 253:0 0 80M 0 disk

A quick and easy way to test if read and write is working is through

fio. Install fio and run the following

command:

$ fio --name=randomwrite --ioengine=io_uring --iodepth=16 --rw=randwrite \

--size=80M --verify=crc32 --filename=/dev/blkram

randomwrite: (g=0): rw=randwrite, bs=(R) 4096B-4096B, (W) 4096B-4096B, (T) 4096B-4096B, ioengine=io_uring, iodepth=16

fio-3.31-8-g7a7bc

Starting 1 process

randomwrite: (groupid=0, jobs=1): err= 0: pid=968: Mon Dec 5 18:23:19 2022

read: IOPS=62.1k, BW=242MiB/s (254MB/s)(80.0MiB/330msec)

slat (usec): min=6, max=195, avg= 7.80, stdev= 2.08

clat (usec): min=8, max=444, avg=241.21, stdev=10.61

lat (usec): min=15, max=452, avg=249.01, stdev=10.85

....

write: IOPS=78.8k, BW=308MiB/s (323MB/s)(80.0MiB/260msec); 0 zone resets

slat (usec): min=9, max=194, avg=12.22, stdev= 5.38

clat (usec): min=20, max=1165, avg=190.17, stdev=68.66

lat (usec): min=31, max=1176, avg=202.39, stdev=73.00

....

bw ( KiB/s): min=163840, max=163840, per=52.00%, avg=163840.00, stdev= 0.00, samples=1

iops : min=40960, max=40960, avg=40960.00, stdev= 0.00, samples=1

lat (usec) : 10=0.01%, 50=0.01%, 100=0.02%, 250=89.26%, 500=10.23%

lat (usec) : 750=0.48%

lat (msec) : 2=0.01%

cpu : usr=48.15%, sys=46.11%, ctx=1390, majf=0, minf=573

IO depths : 1=0.1%, 2=0.1%, 4=0.1%, 8=0.1%, 16=99.9%, 32=0.0%, >=64=0.0%

submit : 0=0.0%, 4=100.0%, 8=0.0%, 16=0.0%, 32=0.0%, 64=0.0%, >=64=0.0%

complete : 0=0.0%, 4=100.0%, 8=0.0%, 16=0.1%, 32=0.0%, 64=0.0%, >=64=0.0%

issued rwts: total=20480,20480,0,0 short=0,0,0,0 dropped=0,0,0,0

latency : target=0, window=0, percentile=100.00%, depth=16

Run status group 0 (all jobs):

READ: bw=242MiB/s (254MB/s), 242MiB/s-242MiB/s (254MB/s-254MB/s), io=80.0MiB (83.9MB), run=330-330msec

WRITE: bw=308MiB/s (323MB/s), 308MiB/s-308MiB/s (323MB/s-323MB/s), io=80.0MiB (83.9MB), run=260-260msec

Disk stats (read/write):

blkram: ios=11148/661, merge=0/19819, ticks=18/1238, in_queue=1256, util=42.53%

The above fio command will send random writes to the device, and at the end verifies (by reading) if the device contains what was written.

Conclusion:

A simple RAM-backed block device driver was explored as a part of this

article. The main idea behind writing this is to understand the blk-mq

framework provided by the block layer stack and write a device driver

using it. There is a lot of knobs that blk-mq offers which is not

covered in this article that could be utilized to optimize the driver

depending on the device.

I highly recommend the reader to clone the example from

github and play with it in QEMU.

I already have an article about using QEMU for NVMe development, and it can

be used to easily create a virtual machine with QEMU.

The best way to explore is by using the trace-cmd2 utility or just with debug prints in

the kernel to see how different blk-settings affect the request sent

to this device.

I hope you enjoyed the article. Happy Hacking!

1 LWN article about block layer part1 & part2

2 Learning the linux kernel with tracing video

3 what happens when kmalloc is used instead of kvmalloc:

Kernel panics when kmalloc is used instead of kvmalloc for

40 MB of data_size_bytes:

WARNING: CPU: 0 PID: 3467 at mm/page_alloc.c:5527 __alloc_pages+0x48b/0x5a0

__alloc_pages+0x48b/0x5a0 corresponds to the following line in the

kernel:

$ addr2line --exe=vmlinux --functions __alloc_pages+0x48b

__alloc_pages

linux/mm/page_alloc.c:5527 (discriminator 9)

Looking at the code at mm/page_alloc:5527:

#define MAX_ORDER 11

....

....

/*

* There are several places where we assume that the order value is sane

* so bail out early if the request is out of bound.

*/

if (WARN_ON_ONCE_GFP(order >= MAX_ORDER, gfp))

return NULL;

Any request of kmalloc with order 11 or above: 2^10 * PAGE_SIZE (4096 for x86)= 4 MB

will fail this check.